Why Apple Watch When We Already Have iPhone?

After Apple’s keynote event last September where they unveiled Apple Watch, a lot of people jumped to the wrong conclusions. There was a lot of criticism about Apple’s “storytelling” — or lack of it — during the reveal, where the company was rightfully panned for their choice to focus too much on the allure of Apple Watch’s hardware instead of highlighting the actual utility of the device. Plus, it’s a watch, right? In an era where watches seem to have been killed by the smartphone itself, people are skeptical. Why does Apple Watch exist? What problems does it solve?

Forget What You Know

To grasp the true potential for Apple Watch (and, more generally, other wearables), you must first reset your understanding about Apple Watch itself. Try to forget everything you know about the device. Forget about the seemingly infinite customization options and the ability to detail the alignment of the solar system. Forget about the unknown price of the Edition edition. Forget that Apple Watch is a watch. Because it’s not a watch. Not really. So try to clean the slate, and let’s begin the reintroduction.

Why Wearables?

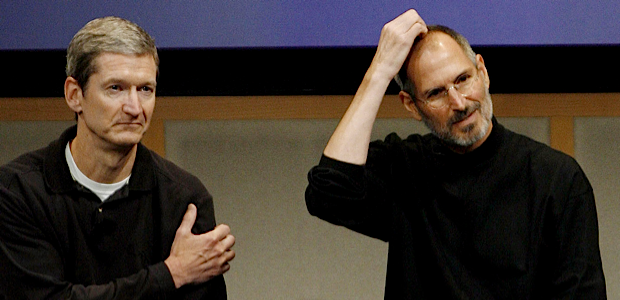

“Every once in a while a revolutionary product comes along that changes everything. … Apple’s been very fortunate in that it’s introduced a few of these.”

Steve Jobs said that when he introduced the iPhone in 2007. Apple did the same thing with iPad, and now, again, with Apple Watch. And they’ve done it by staying true to their roots as a personal device company. Yes, they started by making “personal computers,” but the term was shackled by the mainstream to bulky desktop and laptop workstations. That didn’t work for Apple’s plans going forward. In fact, around the time of iPhone’s launch in 2007, Apple dropped “Computer” from their company name. The point was clear: Apple always was, is, and will be a personal device company.

But Apple’s already given us iPhones, iPads, and Macs. Do we really need a wearable? Is the wearable really the logical conclusion (so far) to the “personalization” of the electronic device?

Given the company’s minimalistic design philosophy, that certainly seems to be the case. In their poetic mission statement, Apple explains that they’re uniquely interested in “the experience of a product,” the way “it makes someone feel,” whether or not it will “make life better.” A product, they say, has to “deserve to exist.” Apple ends with why they sign each product “Designed by Apple in California”:

We’re engineers and artists,

Craftsmen and inventors.

We sign our work.

You may rarely look at it.

But you’ll always feel it.

This is our signature.

And it means everything.

The Apple Watch is Apple’s signature. You may rarely look at it, but you’ll always feel it.

Mobile computing on smartphones and tablets is the new normal. Once upon a time, these devices freed us from our cubicles and home offices, but since they’ve replaced the static workstation, people are now finding themselves similarly chained to their iPhones and iPads. In order for Apple to create a wearable that “deserved to exist,” they had to identify all the ways the mobile experience was less than ideal. Of course, Apple isn’t too prone to being loose-lipped, and they aren’t itching to tell the world (or their competition) exactly what all those problems actually are. At least, not yet, and certainly not like Steve would have done. So, for us to understand Apple’s next step, we had to identify the basic aspects of the mobile experience that could use improvement. What experiences, while possible on iPhone, do not cross the threshold of being engaging on such a device? We came up with five obvious “tentpoles” where phones in our pockets produce (or retain) enough friction to make them fall short:

- Awareness — The world is becoming more and more interconnected. Today, we have iBeacons shooting us information regarding our physical locations, our thermostats and refrigerators are becoming “smarter,” and contextual data has never been more abundant. So far, our phones have served as the conduit for all these interactions. The problem with this is that in order to truly take advantage of the advancements in information technology, we’re stuck holding our phones all the time. We’re consistently shifting our attention back and forth from our handsets to the things they’re supposedly “helping” us be more aware of. If Apple wants to make a wearable, it will have to address this apparent irony better than iPhone already does.

- Interaction — Today, not only are we getting information about the world around us, but we can also interact with and control the world around us. We’re using our phones to control the lighting and music throughout our homes and to actively send all kinds of updates to our various social networks. The issue with the way we’re currently doing these things is that the established methods require us to dig out our phones, find the proper apps, make our quick interactions, and then put our phones away again. As phones are getting bigger to further establish themselves as our primary computing devices, they fly in the face of our basic desire — and our basic need — for small remote control devices and the stripped-down, easy, quick interactions the offer. So how can Apple keep our phones big but our input devices small and our interactions swift?

- Intimate communication — There is no denying that the iPhone has revolutionized communication. From visual voicemail and iMessage to all the world-beating messaging apps on the App Store, it’s incredibly easy to stay in touch. But even with all the seeming complexity that entails, we’ve seen over and over again that what people really want is to keep communication as simple as possible. Most users forego long phone conversations for text messages, and now, most of them are leaving texts behind for lighter-weight services like Snapchat. Communication is getting faster, but we end up trading personal intimacy for all that speed. Apple has tried to merge this ease of communication with the requisite intimacy we all so desperately want. The newer versions of iOS offer FaceTime, personalized audio alerts, and custom vibrations. But the problem we’re seeing with these attempts on smartphones and tablets is that they don’t pass the usability threshold to warrant the effort involved, with the obvious result that only a comparative few users actually use any of this stuff. There is a definite unmet desire in the mobile realm to communicate faster, with less interruption, and with much more intimacy.

- Personal identity/security — Our mobiles today are the hubs of our digital presences, and they contain many parts of our identities. Our passwords, our credit cards, and even our digital keys are now stored in our phones. It’s incredible to be able to wave your phone at a cash register and have the transaction complete almost before it ever started. This concept of phone-as-identity is just beginning, and any new type of mobile product has to accelerate that movement, not hinder it. Instead of fishing your phone or wallet out of your purse or pocket, there should be a way to make this digital identity more convenient and more secure.

- Personal health analysis/monitoring — The final trend we see today is that people are more and more health conscious. And this isn’t just limited to athletic types competing in triathlons and crossfit competitions, either. We see average Joes and plain Janes trading in their french fries for kale chips and checking their iPhones to make sure they’ve taken enough steps to meet their fitness goals each day. There lately seems to be a general awareness about personal health that’s focusing in on the importance of physical maintenance. The problem modern mobiles face now is: How can our devices be improved to be more accurate, more aware, and more understanding when it comes to our personal health and fitness needs?

If these are the shortcomings that exist in our current mobile experience, the next task Apple had was, obviously, to figure out how to improve them. To do that, they had to start with the notion that any new device needed to be constantly available and incredibly accessible. An iPhone buried in your pocket, purse, or backpack is hardly ideal for any of the identified tentpoles above. Maybe the first option Apple tried looked something like this:

That’s pretty silly, and — so far — it’s been a technological nonstarter. (See you around, Google Glass!) Plus, there was an easier answer, and it’s been staring everyone in the face for a really long time. Bloomberg explains how Apple lead designer Jony Ive figured it out:

Ive, 47, immersed himself in horological history. Clocks first popped up on top of towers in the center of towns and over time were gradually miniaturized, appearing on belt buckles, as neck pendants, and inside trouser pockets. They eventually migrated to the wrist, first as a way for ship captains to tell time while keeping their hands firmly locked on the wheel. “What was interesting is that it took centuries to find the wrist and then it didn’t go anywhere else,” Ive says. “I would argue the wrist is the right place for the technology.”

So, based on hundreds of years of human experience, there was only one place to put such a device: the wrist.

It turns out that, by putting a personal device on your wrist, you can solve those five tentpole goals in an extraordinary way — a way that you can’t solve with something that lives in your pocket and has to compete for your attention. But once the location was settled, there was still the matter of size and UI to consider. Nobody wants to be this guy (although I admit that Leela and the Predator are both excellent role models):

In addition to looking absurd (and absurdly uncomfortable), such a setup wouldn’t actually solve any of our many problems with current phones and tablets. It wouldn’t do a single thing to address the above tentpoles. Instead, Apple had to identify the most important technological shortcomings of the current state of the art, and they had to do it in the context of a massively shrunken down user experience. They had to focus on making things more efficient and way more comfortable. Apple Watch had to be tiny. But even on a wearable device, software is as big a part of the equation as hardware. Tim Cook explains this in the simplest terms:

What we didn’t do is take the iPhone and shrink the user interface and strap it on your wrist.

A Breakthrough In UX

Apple Watch doesn’t go the above route. Instead, the company spent the time and money to research and reimagine the entire established model of the actionable mobile GUI. It was a sticky mess to be sure, but the company seems to have cracked the code. In settling on a small, traditional, comfortable, wristwatch-sized device, Apple set about to make sure that Apple Watch:

- Is always on you, with nothing to hold. There is no better way for a device to solve the awareness problem than by offering a built-in way to communicate that doesn’t actually require you to use your hands or hold onto something while you’re trying to do something else. With Apple Watch, the beacons of information and notifications coming your way will add to — and not compete with — the overall experience, allowing you to be more aware of your actual, real-world surroundings instead of being distracted by information overload.

- Is never more than a glance away. This tiny, always-accessible device is perfect for quick interactions and controls because all you need to do to use it is raise your arm, look down, and take a “glance” at your custom notifications. This system — which Apple actually calls Glances — is a streamlined way to get quick access to the information you want without having to launch an app.

- Allows communication through touch. Touch, perhaps the most intimate of all the senses, has never been fully represented with modern technology, mobile or otherwise. Finally, Apple Watch is allowing us to use physical touch as a true communications platform. Through its vibrating Taptic Engine module, Apple Watch will “tap” you in different ways to “tell” you different things. It allows users to communicate with each other in new ways, like sending customized force feedback to your contacts — that is, sending them messages they can actually feel. You can even send little doodles to Apple Watch-wearing acquaintances, which they’ll be able to see and feel on their wrists. The smallest subtleties of communication are often the most emotional and important, and Apple Watch promises to open up a whole new language for its users.

- Is aware of your presence via constantly monitored contact with your skin. If iPhone’s fingerprint scanner’s ability to replace passwords was game-changing, this concept is nothing short of revolutionary. With Apple Watch, you don’t even need your fingerprint. Instead, the wearable uses your heartbeat’s presence as an authorization system itself. (Bear in mind, it doesn’t use your heart’s actual unique biorhythm as an identifying characteristic, just the existence of that rhythm. If you remove Apple Watch, the presence of your heartbeat goes away, and you’ll have to re-verify the unit before this system will work properly again.) From there, you can buy your goods, unlock your doors, turn on your lights, start your car, and anything else you (or a good developer) can imagine, all without having to reach into your pocket or dig through a cluttered bag. It’s the next step in unifying your physical self with your digital presence.

- Can monitor your movement and heart rate to provide fitness feedback. With its heart rate sensor and other motion sensors, Apple Watch is set up to be the king of fitness trackers. The actual health industry is also using the device, potentially allowing for better triage care and vitals monitoring in doctor’s offices and hospitals. Apple’s HealthKit program is already making serious inroads across the country, and the pilot programs have been met with tremendous enthusiasm. Expect Apple to seriously change the landscape of the health and fitness industries in the next few years.

A Revolution In UI

Apple Watch, being so small and so intimate, necessitated some new elements to make it effortlessly functional, and much of Apple’s multi-year R&D was focused on the new user interface required. Several major problems had to be solved.

- Problem: The screen can’t always be on. That’s a distraction (the antithesis of Apple Watch), and it’s a massive battery drain.

Solution: Apple spent an incredible amount of time and effort studying human movement in order to design a toggle that can tell the difference between a device-waking wrist glance and all the other movements the body makes during the day. Apple Watch wakes up and displays information only when you want it to.

- Problem: For notifications on such a non-distracting device, ringers, alerts, and loud vibration motors are the opposite of what anyone wants or needs.

Solution: Haptic feedback, provided by way of Apple’s Taptic Engine.

- Problem: Pinch-to-zoom and multitouch are the gold standards by which we interact with our iPhones and iPads. But on a screen this small, our fingers cover the majority of the screen and block the content. It just doesn’t work.

Solution: In addition to being a traditional fashion cue, Apple Watch’s Digital Crown is used as a home button, document scroller, and zoom system all in one.

- Problem: There is no room afforded to various UI buttons that allow the user to call up different sections of an app quickly (à la the navigation bar in iOS). Having to endlessly scroll through multiple sections and submenus is inefficient and frustrating.

Solution: Apple has invented a new touchscreen input mechanism called Force Touch. With this, Apple Watch can tell a tap from a press and call up different sections, options, and actions accordingly.

A Throwback To Fashion

Last and, frankly, least (but least is still important), Apple Watch is — and in fact needs to be — a fashion accessory. When we are asked to wear something, what we wear should have the ability to reflect our personalities and personal styles. Who wants to be limited to a one-size-fits-all T-shirt? Apple Watch comes in so many versions not due to some lack of focus or simplicity on Apple’s part, but because people are of different sizes and tastes. There are large wrists and small wrists. There are kids and adults. There are bodybuilders and businessmen and fancy dinner hostesses. If Apple Watch is to be a part of your everyday life held right out in the open for all to see, it has to appeal to a wide array of people and personalities. It seems to do that pretty well.

Why So Many Skeptics?

Many critics and nay-sayers are choosing to focus on Apple Watch’s initial perceived constraints. It is very true that the opening version of WatchKit (Apple Watch’s SDK) is limited, especially compared to the powerhouse options of iPhone. It is also very true, however, that constraints fuel innovation. Apple Watch will not be defined by how well it reproduces the apps and experiences of iPhone, but rather by the new kinds of apps and experiences it enables. Ultimately, what Apple Watch is can be identified by what it isn’t. What was iPhone when it first launched? And what was iPad? To figure out the limits of Apple Watch, look not to the things it can do, but look for the things it can’t. Then figure out why not, and ask yourself if maybe — just maybe — version two will be able to remedy that shortcoming.

A pretty smart guy once said, “People don’t know what they want until you show it to them.” Come April, you’ll be able to see Apple Watch for yourself. Just make sure you bring your wallet.

It might be the last time you’ll ever need it.